| ||||||||||||||||||

|  |  | ||||||||||||||||

|  |  |  | |||||||||||||||

| ||||

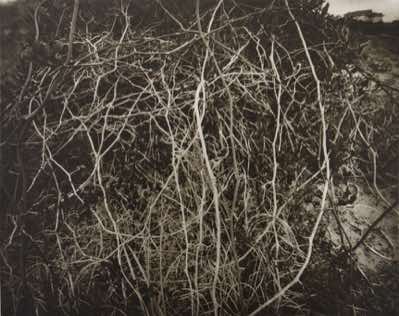

Opening talk – The Alchemists by Sue Forster gold street studios, 20 November 2016 Welcome to ‘The Alchemists’, an exhibition of copperplate photogravure by three very special artists: Jennifer Page from North Carolina, USA, and Dianne Longley and Ellie Young from Trentham. As Jennifer’s work dominates this exhibition you will not be surprised to learn that it was the catalyst for Ellie and Dianne’s recent photogravures. Jennifer is a photographer who specializes in copperplate photogravure and is acknowledged as a master in this field. Ellie has travelled to Jennifer’s Cape Fear Press studio to participate in her workshops and still retains close links with her. Ellie is also recognised internationally as a guru of diverse and little known photographic processes, and she now teaches copperplate photogravure from gold street studios. Unlike the other two artists, Dianne Longley is known internationally as a printmaker, the distinction being that photography is one component of her prints, which also incorporate drawing. Like Jennifer and Ellie, she is well known as a teacher, particularly for her pioneering work in photopolymer printmaking and her book on the subject. Having developed her own distinctive iconography of fantasy characters, she now applies these to many different media. All three women are highly skilled and well organized, with multiple strands to their busy art careers. Having followed Ellie and Dianne’s careers for around twelve years, I can vouch that they are both digitally savvy and very good scientists as well as artists. So I was curious about how they collectively became ‘The Alchemists’. Derived from the Greek word khēmia (khēmeia), meaning the ‘art of transmuting metals’, alchemy was a speculative philosophy and the medieval forerunner of modern chemistry. Alchemists aimed in particular to convert base metals into gold or to find a universal elixir for prolonging life. Although alchemy is referred to as an occult science with links to astrology, the term is also linked to magic, perhaps because of the underlying mysticism associated with its secret processes. The magical goal of alchemy is, after all, to turn a common substance, usually of little value, into a substance of great value. Historically, the dark inky arts of printmaking developed in tandem with the occult science of alchemy. When I visited this exhibition earlier in the week, Ellie confirmed that photogravure is a particularly complex technique, due to the number of processes and variables involved. Despite standard testing, the final print may still appear as a miraculous revelation, even to the artists themselves! I realized then that it would also be a miracle if I could describe the technique at this opening! So, if you have technical questions, please refer them to Ellie or Dianne or check out Ellie’s workshop schedule. However, I can tell you that photogravure was developed as a photo-based etching technique during the nineteenth century, principally by Henry Fox Talbot in England and Czech painter Karel Klic. Their goal was to transfer photographic images onto metal plates so that they could be editioned using a regular intaglio printing press. In the early twentieth century Alfred Steiglitz perfected the technique for his photographic quarterly ‘Camera Work’. Luckily Ellie has prints by Stieglitz and his contemporary Edward Steichen in her collection, and you can see these today on the wall of her studio. The technique of photogravure involves placing a continuous tone film positive over a sensitized sheet of gelatin tissue, and exposing the layers to ultraviolet light. The gelatin hardens according to the amount of light passing through it. To create plate texture to hold ink, the gelatin tissue is also exposed to an ‘aquatint screen’ or an aquatint grain can be applied directly onto the copper plate. The gelatin tissue is adhered to the plate by applying pressure, and the plate is washed to remove unexposed gelatin. The dry hardened gelatin on the plate surface forms a resist when the plate is placed in a series of ferric chloride baths, of various strengths. Afterward the plate image can be inked and printed. Photogravure is valued for the subtlety and richness of its tonal range, including its velvety blacks, which are the result of variable depths of etching in the ferric chloride. Humidity, temperature, chemical concentrations and light intensity all need to be carefully controlled during every stage to prevent undesirable chemical reactions. Let me tell you about my own alchemical reaction to these photogravures, starting with Jennifer Page’s sophisticated land and seascapes that build on historical tradition. These are technically virtuous prints of great tonal subtlety. I understand that Jennifer shot her sea and shore photographs in RAW mode using a Panasonic Lumix camera and as JPEGs using an Olympus waterproof camera, and their prints were made from plates treated with Picco dust grain. The other four images which appear in closer focus – Smoke, Dune Flower, Thicket and Vines – were shot with a homemade pinhole camera and contact printed onto lith film to make positives. They were processed using Jennifer’s handmade aquatint screens and natural sunlight. To view Jennifer’s pinhole camera and read more information about her processes, you may like to see her Cape Fear Press website. It also provides a great introduction to the breadth of her artistic practice. Jennifer’s Artist Statement for this exhibition draws a close connection between her imagery and technique. She writes that the ‘elaborate process’ of photogravure and the way its ‘elements and materials interact’ is ‘a microcosm of nature itself’. I would also suggest that light and shade, pattern and form, ebb and flow, is as much the subject of her prints as the actual event or place that has been photographed. Jennifer likens the act of finding balance and truths in her work to alchemy. Inspired by Jennifer’s seascapes, Ellie developed a complementary theme for her own photogravures, with sea creatures as her subject and a non-traditional blue-black ink to create a visual link to their watery origins. She used a Hasselblad camera and analogue film to take studio shots of these creatures against a simple paper roll background. In common with her salt and carbon prints, they demonstrate Ellie’s discerning eye for the sculptural and textural beauty of organic forms, and her marvelous ability to transform them into objects of wonder through photographic processes. Like Ellie, Dianne has made subtle use of colour in her four small photogravures combining line drawing with a photographic background of clouds. Two are printed in blue-black ink over pink chine collé, and the other two in red-brown ink over pale-green chine collé. These magical, unstable floating worlds are populated by primordial plants and a burlesque assortment of monsters, grotesques and ridiculously cute characters, all apparently deep in conversation. Sourced from medieval mythology, sixteenth-century European prints and contemporary Japanese ‘kawaii’, Dianne’s surreal creatures play out open-ended stories. Just like life itself, their meaning remains unclear. Whereas Jennifer and Ellie’s prints show traces of our organic material world, Dianne’s prints simultaneously supplant the real and revel in their trickery. But each print has it’s own combination of science and magic. To conclude where we began, here is our alchemy: common matter transmuted into artistic gold through the science and craft of printmaking and the magical filter of the artist’s imagination. I’d like you to join with me in congratulating the artists on this exhibition. I hope you all enjoy it as much as I have and will feel encouraged to give these beautiful prints a home in your own collections. Correction: The photogravure titled 'Smoke' was photographed with a digital camera in RAW format, not 8x10 pinhole. | ||